Blog 4 – Liz Coman, Assistant Arts Officer Dublin City Council & VTS Facilitator

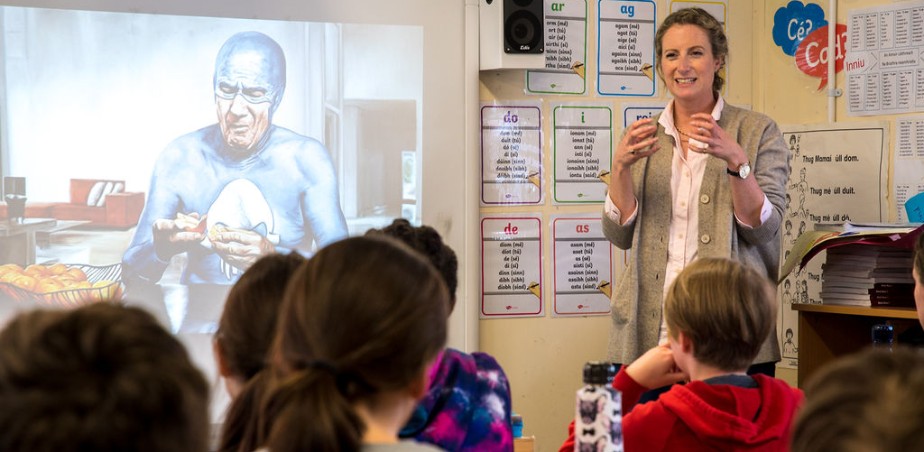

Image: Primary School Teacher, Jane Malone

Liz Coman is an Assistant Arts Officer with Dublin City Council. She is a certified Visual Thinking Strategies facilitator with VTS/USA and has completed training to coaching level. She is responsible for monitoring the quality of Erasmus+ Permission to Wonder – an EU project for Dublin City Council that is testing the VTS training pathway with educators in classroom and gallery settings. Liz has a background in History of Art and Museum Studies and fifteen years experience in designing innovative projects that support arts, education and learning. She has led trainings in enquiry led approaches to mediating artwork for visual art facilitators in The Ark, A Cultural Centre for Children, The National Gallery of Ireland, and The Turner Prize, Derry and offers ongoing mentorship for individual artists, arts educators and teachers.

“Observation is more than one thing – we use our eyes to analyse an image, and we also use thinking, and our senses and emotions to interpret what we are seeing” – Erasmus+ Permission to Wonder

A Conversation with Primary School Teacher, Jane Malone

For this fourth and final blog about Erasmus+ Permission to Wonder, it is timely for me to reflect on some of our learnings from the VTS training pathway for educators. Over 150 educators, from classroom and museum settings, were supported to access the VTS training pathway with VTS/USA. This happened, through a partnership approach that allowed a range of partners across local, national and European to fund a unique training programme.

The research evaluation framework for Erasmus+ Permission to Wonder will capture the ‘impact’ of the VTS training pathway on educators training and practicing VTS in schools and museums across. Findings will be presented by VTS Nederland at our Erasmus+ Permission to Wonder Conference on 21 April 2020 in Dublin Castle.

Between now and then, we are considering what is next for our work with VTS. What are the existing mainstream teacher and artist training pathways that could offer support to the VTS training pathway? How do we hold on to the value of peer to peer learning across a the mixed cohort of educators – artist, art educators, secondary (art) teacher and primary school classroom teachers? How do we support mixed groupings of trainees to continue to access enjoyable and deep VTS learning experiences about art, learning, classroom and community where every individual voice is valued and heard?

The cross-disciplinary potential for VTS is striking. Art is the starting point and the transferrable skills for the trained VTS educator and for the participating group become more and more obvious with regular practice. For me, the most obvious win for VTS practice is within the primary school or early years classroom. In these classrooms, multiple subject areas sit alongside each other, but objectives for building patterns of learning, thinking and communicating are overarching priorities. This is approach to learning is more and more mirrored in the modern workplace. Artists, lawyers, farmers, employees and entrepreneurs across all disciplines must show flexibility in their thinking and their approach to running their business/getting their product out there/meeting their client needs. Problem solving and team communication skills are key in order to do that. Teams must use their observational skills and thinking skills in tandem with a bigger picture approach which is supported by being open to differing points of view, to allow for benefit from other people’s experience along with their own.

Below, Jane Malone, a primary school teacher from St Catherine’s NS, Donore Avenue, talks about how VTS has strengthened her practice in facilitating students’ learning; how this practice is a tool for communication skills, such as deep listening and respectful discussion; how it is a tool for opening students up to their own thinking processes to support how they learn, access knowledge and problem solve; how this practice can transfer from art, to maths, to science to SPHE, to oral language development, to project development.

What do you find VTS brings to your practice as a primary teacher?

In a primary school classroom of today, we are facilitators of learning, more so than the traditional idea of teachers. VTS definitely highlighted to me the skill of being a facilitator. You facilitate the thinking skills you want them to have or the writing skills you want them, but where they take it is theirs, as long as it’s appropriate.

I find our VTS sessions are a great tool for demonstrating and practising active listening. When someone is making their observation, and when I’m paraphrasing back, they are all listening. Their hand isn’t up with their point, it’s a shared listening experience where they can see what the speaker is seeing. That has really helped in terms of general classroom management, but also for turn taking in terms of respectful conversation. This is something that can’t be explicitly taught. At the same time, it permeates all the other lessons, because we all get so used to the process.

I also find our VTS sessions very inclusive, because it’s not about ability, it’s about the picture or the piece of art that you were looking at, and ‘my opinion’ is not the rightopinion, it may vary very differently to what ‘your opinion’ is. It’s accessing art on all levels for all children of all abilities, not just for the ‘arty’ children or the people who like that piece of art. It takes how art used to be untouchable, it was in galleries, behind frames, it’s opening it up to multiple possible interpretations.

For me, VTS impacts all the curriculum areas, particularly the language elements and the social and emotional aspect of things as well. I use it with ‘Number Talks’, and with anything I’m doing in SESE where I’m facilitating project-based learning and they’re determining where they’re going to take the project. VTS fits well in particular, with the New Language Curriculum, with Irish and English, and how it describes the role of paraphrasing the students comment, that no comment is incorrect, but the paraphrase back is the teaching and learning moment. The children are becoming more aware of how I am teaching them, more familiar with the paraphrasing process, and this gives them the confidence to make the comment, in a language lesson, without worrying about being right or wrong.

What have you noticed happening in your work in the classroom with VTS?

The group I have this year is sixth class. I had them in fourth class, when I started practicing VTS in the classroom. So this year, when I do VTS with the children, I begin a session by talking with them about the broad concept of thinkingthat happens when we do VTS – ‘what is observing?’ We talk about using our eyes, and the role of listening. We go deeper with an art image and talk about how we use our senses to observe, and also how our emotional response informs our thinking.

I began this year’s science curriculum with an exercise where we took a roll of Sellotape and passed it around the room. Each child had to make an observational comment about it, as it was passed from person to person. The reason why I blended VTS with this exercise, is because in VTS with art images, you are naturally talking about story, setting, materials, bringing in previous experience and knowledge. So, in this Sellotape exercise, I was really conscious that it can push them to build more sophisticated language for what they are describing. I keep my paraphrasing conditional and label the thinking processes so that the children can recognise that their thinking processes can transfer from the VTS exercise we do with art, to this exercise, which is more about introducing scientific language for observation. It’s a really successful exercise because you can hear them talking about texture of the Sellotape, using language to describe it based on their senses, describing it’s shape based on their knowledge of maths, making metacognitive statements that are bringing information from other bodies of knowledge.

I see that this is how I am going to bring my VTS practice forward. In the classroom, I’m trying to create an atmosphere of STEAM versus STEM. VTS is one of the methodologies that supports me to do this. I use mind maps and Elklan (a process to meet the speech, language and communication needs of children) with topics where we build vocabulary and language. I find VTS coming into play more for the more technical curriculum subject areas such as the literacy skills of breaking down a language, looking at and attempting maths problem solving, and also for science.

How important do you think that silence at the beginning to observe is?

Very. But we do that in another form in our ‘number talks’ as well, so you put up your number sentence and then you literally wait. It’s very hard when you’re initially doing it as a teacher, to wait long enough, standing in silence is quite difficult. Because we had been doing it in ‘number talks’, I was then able to marry it, so I give them quite a bit of time. It does occur to me each time I do it “I wonder how long everybody else gives?” Sherry Parrish is the number talks guru, so if you watched one of her videos you’d understand the similarities. It’s “how would you do this?”, “how did you come to your conclusions?”, “now, tell the rest of the class how you got that answer or why you went that way” or “what does everybody else think of the way X did that sum?”. So again, it’s similar a similar process of supporting thinking and social learning.

Can you recall a favourite VTS Image Discussion?

One of my favourite VTS sessions was when I was practicing on the Permission to Wonder training in Helsinki. I was looking at the image for the first time and not sure where it would go with the group. There were many different interpretations of the image from individuals and so I had to really concentrate on my paraphrasing. It showed me that my paraphrasing was really working well for me, I was hearing as I was speaking. It was really challenging, but there seemed to be a flow. I remember this as I learned so much from it.

Another one that sticks out in my mind, with sixth class last year, they kept on trying to identify the images as being staged. ‘Oh this has been deliberately set up as though it was in the 1960s and it was deliberately provocative because….’ – they were really cynical about the image and it felt like there was an inflexibility of their engagement with it. They were more about creating the backstory about why the artist did it, than observing what it was in front of them. I found that really interesting.

One other one, was a picture of a woman in a subway surrounded by a lot of men. She is to the foreground, and one of the children that has anxiety identified it as her experiencing great anxiety and nobody around her knowing it. So that kind of projecting their own emotional states onto the images we are looking at, I find that really interesting.

It sounds like for you, in a VTS image discussion you are observing the ‘thinking’ going on – either your own thinking or the students thinking?

It definitely would be part of my practice as a teacher. We are here to teach skills, in particular to understand that there are thinking processes and to help them to figure out how to support these processes for themselves in the future. So they can access the facts. Who remembers all the rivers and mountains of Ireland, it’s more about how you going about researching that information and your thinking process around researching the question that’s important.

How did Erasmus+ Permission to Wonder support you to develop your VTS practice?

It greatly supported me to put aside my learning and experience and become open to a new way of engaging with languages. I found that really interesting as languages are ‘my thing’. I have a degree in French and Italian, English and Gaeilge are my favourite subjects to teach, and I love grammar, so it was fascinating to me how I struggled with the VTS questions at first. They felt so American and strange to me but when I saw the huge body of research behind them and experienced firsthand how effective they were in keeping a rein in on the facilitator’s natural bias, I was completely converted. It was also really comforting to work with such experienced artists and art professionals and see how my lack of experience did not impede my ability to facilitate a VTS session. Finally, it was an exhausting but really wonderful experience on a personal level. I really feel I grew as an individual and my love of learning was reignited. So thank you to all involved.