Blog 2 – Dr Francesca La Morgia, Founder and Director of Mother Tongues

Language Explorers - Enniscorthy - Mother Tongues

Dr Francesca La Morgia is a linguist, lecturer and researcher. She is the founding director of Mother Tongues where she is responsible for Learning, Research and Policy Development. She has been a lecturer in linguistics in Trinity College, Ulster University, Maynooth University and the University of Reading. She has written on issues related to migration, multilingualism and intercultural spaces. Francesca is an alumna of the second Artist in the Community Scheme Summer School on Cultural Diversity and Collaborative Practice (2019).

Exploiting the creative potential of multilingualism

It is widely accepted that if you express yourself through art there is no “right way”, because art is about exploring all creative possibilities, and not necessarily by following a set path. When it comes to language, our unique and incredibly creative form of human expression, we are often brought to believe that the right way is the one that is “conventional” and that we can master this art only by following rules in a very strict way.

In this blog I would like to dispel the myth that in order to engage with languages we need to be experts, and share some reflections based on the ‘Language Explorers’ initiative.

Language is power

As Frantz Fanon stated in Black Skin, White Masks, “A man who has a language consequently possesses the world expressed and implied by that language. What we are getting at becomes plain: mastery of language affords remarkable power.”

Language has always been the repository of cultural traditions, behaviours and beliefs passed down from generation to generation. Most importantly, language has an influence on how we think, how we behave, socialise and reason. Language is power because when we feel that we are not understood, we feel powerless. When we see that our mother tongue is considered less valuable than other languages, we feel inferior.

Language is power because if you possess the linguistic skills of those who have power you are privileged, if you don’t you face discrimination. So how do we shift and revisit this power dynamic?

Who is the expert in the room?

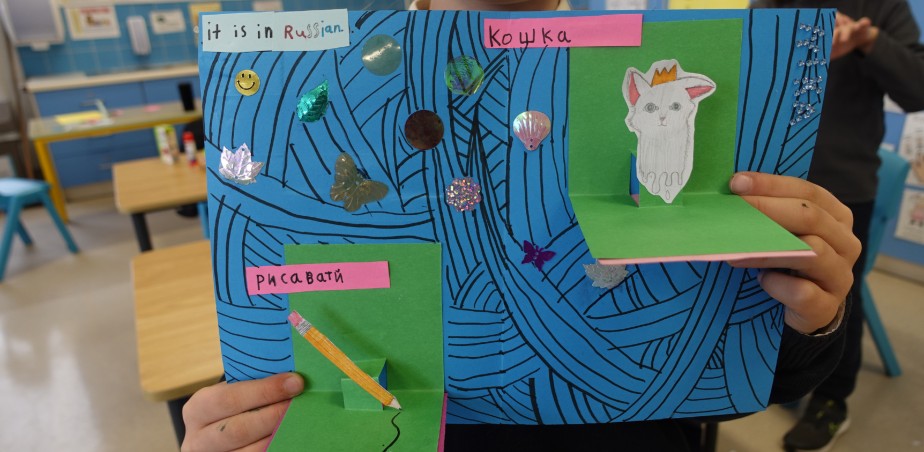

I created ‘Language Explorers‘ to offer children a space to listen to each other’s language stories, to examine the neighbourhood they live in and get to know about languages, sounds and linguistic differences. If I am working with a new group of children, I can’t tell if someone is an Irish speaker and whether the same person can also speak Polish until we get to have that conversation. So, my first step is always based on an initial conversation open to everyone in the group. This often starts with me learning to say each name correctly, a small effort which has always paid off, both with children and parents. The workshops in class vary: we use interactive games, art-making, singing, storytelling, story writing, and more.

The biggest challenge in this work lies in accepting that I don’t know much about other languages, and I have no power to decide what is right or wrong. As described by Phil McCarthy and Annie Asgard in this video, for multilingualism to thrive we need to let children be the experts, and by led by them.

A resource I use is the Mother Tongues podcasts, which carry us straight into the world of multilingual families and offer many points of discussion and reflection. Being in English, they are accessible to all, but they also allow for a short immersion in another language and culture, and the scenarios described will be very familiar to many children. It is quite astonishing to see the reaction of the children when different languages are used or heard in the classroom, and I think this is summed up really clearly in Soraya Sobrevía’s article on her experience.

When talking to older children, I enjoy using George the Poet’s poem Mother Tongue because it goes straight to the heart of the challenge that many young people face. The children’s creative responses to this poem have led us to tears multiple times!

Most of our creative work can become multilingual if we allow languages to emerge from silence. There is no ideal lesson plan, because this is mainly a shift in approach. The task of the person facilitating this work is to accept to be in a state of “not knowing the right answer”, and to make a clear statement that welcomes all languages. It might seem obvious or redundant, but since children are normally not offered this opportunity and sometimes not allowed to use all of their language skills outside of their home, this needs to be a clear statement of intent.

You will need to say that your space welcomes all languages, and to show in your own personal way that you are keen to have multilingual poems and songs, that you would like a bilingual dialogue in your next play, that you will regularly offer a creative space where no language is excluded or marginalised, and where English is not your only priority.

Once you create a space for every language to be unleashed and used as a powerful creative tool, you will notice that children will do the rest, and the change you have brought about will be long lasting.